Mary’s Room: The Thought Experiment That Challenges What We Know About… Knowing

What does it really mean to “know” something? Can knowledge be reduced to facts, or does true understanding require lived experience? To explore this, philosophers often turn to a fascinating thought experiment known as Mary’s Room. Originally proposed by Australian philosopher Frank Jackson in 1982, Mary’s Room (also called the Knowledge Argument) has become one of the most famous thought experiments in philosophy of mind. It challenges the limits of scientific knowledge, raising deep questions about consciousness, experience, and the nature of knowing itself.

NON-STOIC PHILOSOPHIES

9/19/20252 min read

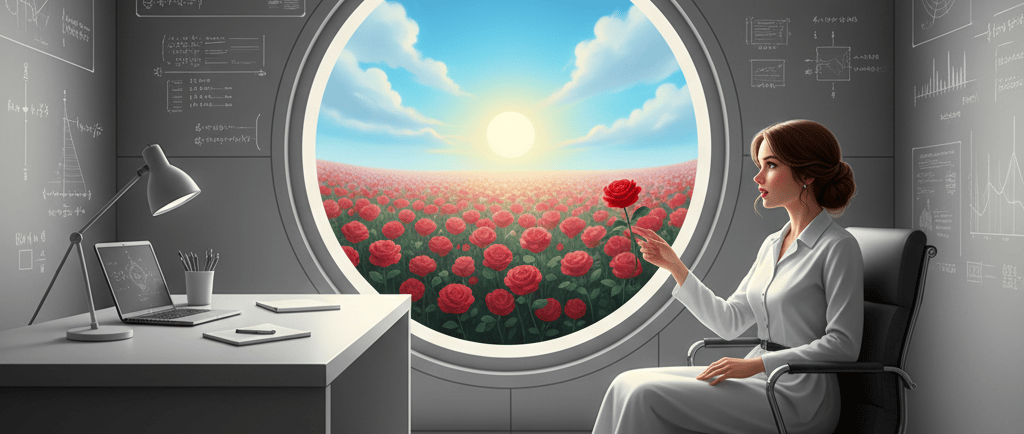

The Story of Mary’s Room

Imagine Mary, a brilliant scientist who knows everything about the color red:

She has studied the physics of light, the biology of vision, and the brain’s response to color.

She knows all possible scientific facts about how humans perceive red.

But there’s a twist—Mary has lived her entire life in a black‑and‑white room, only seeing the world in shades of gray.

Then, one day, Mary steps out of the room and sees a red rose for the first time.

Here’s the key question: when Mary experiences the color red, does she learn something new that she didn’t know before?

The Knowledge Argument

The Mary’s Room thought experiment is often used to argue that:

Knowledge of facts is not enough. Mary had all the scientific data, but she lacked the lived experience of seeing red.

Qualia matter. Philosophers call these subjective experiences qualia—the “what it feels like” aspect of being conscious.

Consciousness might not be fully explained by science. Even with complete information, we might still miss something uniquely subjective.

This challenges the idea that the mind is reducible to physical processes alone.

Why Mary’s Room Still Matters

Mary’s Room isn’t just a brain teaser—it is central to debates in philosophy of mind, artificial intelligence, and even neuroscience.

For philosophy: It fuels discussion on the nature of consciousness and whether subjective experience can be objectively explained.

For AI research: It provokes the question—can machines ever “understand” experiences like humans, or will they be stuck in Mary’s Room, simulating knowledge without real awareness?

For everyday life: It reminds us that personal experience often goes beyond facts. Reading about love, travel, or music is not the same as feeling them directly.

Objections to Mary’s Room

Not all philosophers agree with Jackson’s conclusion. Some argue:

No new knowledge, just new abilities. Mary doesn’t gain new facts—she gains the skill of recognizing and imagining red.

Scientific realism. In principle, a complete scientific description of red could include what it feels like to see red. Mary didn’t yet have that assimilation.

The illusion of mystery. Some argue we romanticize experience too much, when in fact it’s just another brain state science can eventually explain.

These critiques keep the debate alive and ensure Mary never truly leaves her philosophical room.

Key Takeaways

Mary’s Room (the Knowledge Argument) asks if knowing all facts equals knowing experience.

It highlights the concept of qualia, subjective experiences beyond scientific explanation.

The thought experiment bridges discussions in philosophy of mind, AI, and consciousness studies.

Final Thoughts

Mary’s Room shows us that knowing isn’t always the same as experiencing. Science and facts give us powerful insights, but some truths seem to exist only in the realm of experience itself.

Whether you find this argument convincing or not, it invites us to reflect on the richness of lived experience—and to wonder if the deepest parts of consciousness may forever escape complete scientific capture.

After all, you can know every fact about color—but seeing red for the first time feels like something entirely different.

Waste no more time arguing about what a good man should be. Be one - Marcus Aurelius

We suffer more often in imagination than in reality - Seneca

Wealth consists not in having great possessions, but in having few wants - Epictetus